read time: approximately 14 minutes

This week I

- Helped to prepare the Center for a conference Monday, Sept 22;

- Received emails from CSU about a militia-like presence on campus because of a vigil and protest for Charlie Kirk, who was supposed to speak at CSU on Sept 18;

- Was told by my CSU friends to stay away from City Park (Fort Collins) because of an open carry “rally”? wut;

- Met with several secondary and university instructors this week to co-design workshops;

- Went on my first harrytur to Sweden (grocery shopping just across the border because it is less expensive than in Norway)!

My job in Norway entails a) teaching secondary students about life and culture in the United States, b) working with teachers-in-training in their university coursework, and c) offering professional development sessions to current teachers in secondary schools. There are set workshops I’ve designed that are listed on my Fulbright website, but one option is for teachers to contact me and we can design together a workshop for secondary students, teachers-in-training, and/or current teachers.

About half the workshops I have conducted or am preparing to conduct are ones that are co-designed with teachers and instructors. And that has become for me one of the most fun parts about this gig. We usually go to coffee or on a walk, and I ask the teacher about their class, their learning goals, the topics the students have been most engaged with so far this semester. I ask them what questions are coming up for the students about what they’re learning about, especially when it comes to content about the United States. They have lots of questions! Especially because most of the secondary teachers I’ve met who teach English or who teach about the US have never been there! So they rely on information they find online, or sometimes a couple students in the class will have gone on exchange in the States. I clarify a lot of information in these meetings, and the theme is usually something like, the US is really big and it’s hard to make a general statement about any aspect of the whole country. This week I had to explain to a couple teachers that the US has no national curriculum for schools—the teachers were shocked. The follow-up question: what about by state? Do states have a state curriculum? Nope.

This kind of designed thinking—where I get to brainstorm on the spot the relationship between the students, the theme and learning goals for the class, and what I can teach—is really fun. It’s also become a place where I can design workshops grounded in some of the ideas I’m trying to work out for myself about the United States and my relationship to it.

This week I met with a teacher who told me her 11th grade English students are wondering about identities in the US and where they’re doing work about immigration to the US. Part of their program of study is to watch Gran Torino and it got me thinking about a question that’s almost always in the back of my mind: what does it mean to be American?

This is a question I even think about when living in the US because I am often perceived as not American. I am living proof that Asian Americans in the United States are viewed as perpetual foreigners. Strangers who I meet for the first time ask me the same handful of questions: where am I from? Why do I speak English so well? What am I? How long have I lived in the United States? On more than one occasion, I have been mistaken for international faculty. One time I was even mistaken for an international student. These questions and misperceptions stem from the belief that only people who present as white can be American. Despite all of the rhetoric about the US being a nation of immigrants (and enslaved. And Indigenous peoples already living here who white settlers tried to genocide). The truth is, many Americans have an impression of one kind of person being American.

The irony has not escaped me that I am currently serving as a representative of the United States to students and teachers. For most of the students I meet, I am the first American they’ve ever met. Me, who has had my Americanness questioned for as long as I can remember. The first American my dad met where he grew up in Ubon, Thailand was also a person of color: he was a Black man serving in a branch of the United States armed forces and was stationed in a US military base in my dad’s town. We, too, are the face of America.

Because the workshops I design are meant not only to show Norwegian students a glimpse of American life and culture, but also to offer a mirror to their own life and culture, I could ask the same question here: What does it mean to be Norwegian? From what I have learned from being here during a national election and what students and teachers and others I meet tell me about immigration and xenophobia in Norway, we could have parallel conversations.

One requirement to earn Norwegian citizenship is to be able to communicate in Norwegian. Does language make you Norwegian? I’ve spoken to several students of color who note that even though they speak Norwegian and were born in Norway to immigrant parents, they don’t feel like they are treated like their white Norwegian classmates and peers. In one of our Fulbright Rover orientations / school observations, we had an impromptu session with a teacher from Canada who has Norwegian citizenship. He relayed to us that when his citizenship was finalized he was told (I don’t remember by who) that he might hold Norwegian citizenship, but he will never be Norwegian. The teacher went on to tell us how shocked he was: he was white, blond, blue eyed. If he wasn’t considered Norwegian, what was life like for Norwegians of color?

I know that outward appearance isn’t the only thing that makes Norwegians Norwegians or Americans Americans. But it’s the first thing people see and it sometimes feels like my physical appearance is somehow a qualifying tool for my citizenship status.

Other things that I think about that make an American so

- Our ideas about physical space: how much we think we need it, how we physically move through space as if we owned it. I am not sure if I will ever be comfortable with how close people stand next to me on public transportation or how close they get to me when sliding by me in a crowded grocery store aisle. As an American I prefer a much wider berth.

- Our ideas about personal freedoms: Colorado is a good example of how Americans are often libertarian in their ideas about their rights. In Colorado, we have legalized same-sex marriage, possession of marijuana, abortion, and guns. We don’t have a helmet law, as in, motorcyclists don’t have to wear helmets. Live free or die, I guess, right? But I want rights to my body and my decisions too. I happen to also believe that state and federal governments have a duty in protecting citizens through laws, like helmet laws and gun control laws. We in the US have access to a lot of personal freedoms. Threats to this exist, yes, seemingly now more than ever, and more on that below.

- Our ideas about movement: A US passport affords us tremendous freedom of movement. You can be in almost every part of Europe for three months and never need a visa. When I was living in Morocco, you couldn’t travel to Europe, a mere boat ride away, without a visa. We can get on planes, drive in our cars, in some places take public transportation, and access many places. Our own country is huge and if you have the funds and means to access it, you can see and experience a wide variety of settings, terrains, and ways of life.

- Our ideas about excess: I went on a harrytur this Saturday, which is when Norwegians go to Sweden to shop for groceries because it is way cheaper in Sweden than in Norway. On the way back, my Norwegian colleagues were giving me a hard time about excess in America: house sizes, Costco, one million cereal choices. I mean, they’re not wrong. As Americans, we believe it is our right to have lots of things and lots of space. Capitalism, am I right?!

- Our belief about the idea of America. As Americans, we don’t always agree on what kind of America we should be working toward, but there is an ideal America we have in our minds.

- Our beliefs that there are always ways the United States can be better and improve. The United States, since its founding, has been a place that can be better. That can include more people in who gets to have rights; who gets to have health care; who gets access to healthful food; who gets access to clean air, soil, and water; who gets to have lives of luxury and rest; whose voices all matter.

Things that people think make us American

- A national language. The United States doesn’t have a national language. Many lobbyists and members of Congress have attempted to codify one. All have failed.

- A national religion. You may think we have a national religion because all the Christian holidays are also federal holidays, but we don’t have one.

- A national curriculum. Trump wants people to believe that the federal Department of Education (DOE) is controlling what happens in schools. They don’t. They never have. Before half of the DOE employees were fired, they couldn’t even get every school district to follow national laws about serving all students equally, especially those who have been traditionally underresourced and underserved, like poor students of color and students who are disabled.

- A shared history. There is a history of the United States that we are taught in school. But that history is known to be white-washed, presenting a story of American exceptionalism and a continual linear march toward “progress.” The history we’re taught in school sanitizes and often glorifies the relationship white settler colonists have/had with Indigenous peoples and the realities and effects of enslavement; it downplays xenophobia and the role of minoritized peoples in fighting for rights for everyone. We don’t agree on our history. And, because we are a nation composed of Indigenous peoples, enslaved, settler colonists, and immigrants, we all have a different history of the country.

I’m curious about what you think makes an American an American, and what doesn’t?

The other thing that I’ve been thinking about this week and have now started to design a workshop around in collaboration with another secondary teacher is the tensions of America. As Nikole Hannah-Jones has written about in her 1619 Project, the United States is still fighting for the ideals of democracy and freedom that grounded the country’s establishment. Although lofty goals were set out in the founding documents, the same authors of those goals continued to enslave Black Americans; attempted to colonize sovereign Indigenous peoples; and subordinated women, among others.

We have never been a country that has succeeded in living up to the promises of our founding documents, where everyone can have the liberties and freedoms afforded to white, cisheteronormative, ablebodied, educated, wealthy, English speaking, Christian men. And these tensions of who gets access to rights and privileges is a battle we have been constantly fighting. It’s what we’re fighting over right now in the US: who gets rights? Who gets privileges? This fight is never ending. I have fewer rights now as a woman in the United States than I did when I was born. It’s easier for me in many states to get a gun. A gun. Than an abortion. Perhaps this is what it means to be an American: that we don’t have the opportunity to take our rights for granted and must be constantly fighting for them. Feels exhausting. Perhaps only slightly invigorating.

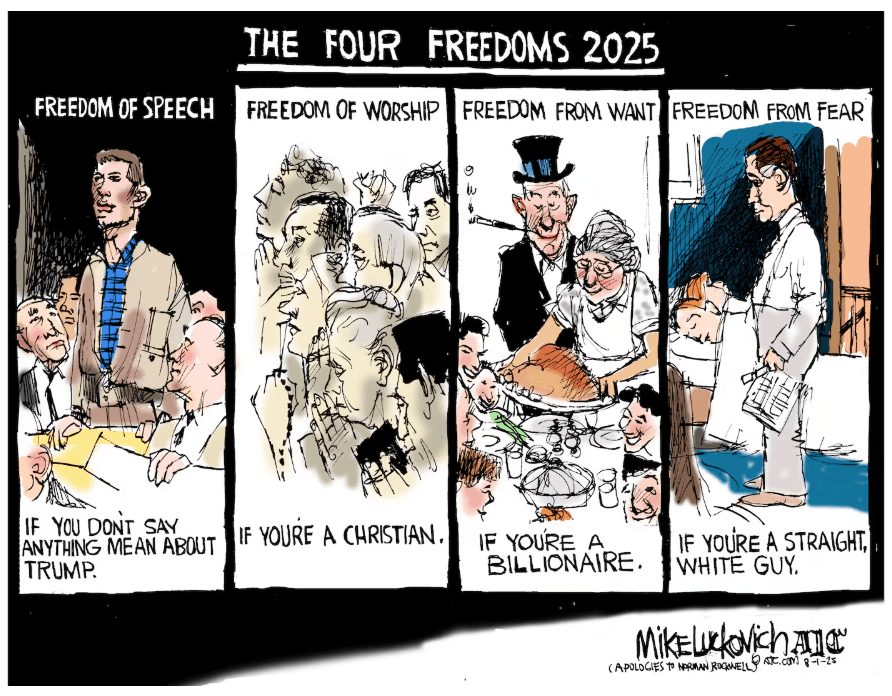

When I taught American Lit we used to read FDR’s Four Freedoms, which he included in his annual State of the Union address in 1941. In 1943, Norman Rockwell painted their visual depiction (they’re all white people!): freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, freedom from fear. One could say that these values identify us as Americans. But we don’t all get these freedoms.

The political cartoonist, Mike Luckovich, who publishes in The Atlanta-Journal Constitution, reprised these for 2025. There is a lot of truth to these new Four Freedoms: who gets these freedoms?

There are many many many things that are frustrating to me about the United States. But I will always call the US my home and I will always stand strong in my Americanness. I deserve the flag of the United States and the protections of the United States Constitution as much as my neighbors in Colorado who are obsessed with Trump. Part of what I love about the United States is the ability to speak out about what’s wrong and to believe that what I do in my work and in my life can make a difference for other Americans, for those who live in the US who haven’t achieved citizenship, and for myself. My daily work is to help build a country where everyone can have their rights that help them actualize as full human beings. Where they can live their dreams and achieve their success. Where they help others to achieve their successes.

We have never been this country, and I know it is scary right now if you live in the United States and aren’t afforded the four freedoms, and/or have limited freedoms. And are watching your freedoms being taken away. But as an American I believe that the country can change. I have evidence of it: people with minoritized identities have fought throughout the nation’s history, for change so that they can have access to what they need access to: medicine and healthcare; workers rights; voting rights; clean air, soil, and water; the ability to control their own bodies; education; rest. I’m not saying that we need to still be fighting this hard. That is absolutely frustrating af. But as an American I believe that we as a country can change. And that the country does change. It might not always feel like it, especially right now when the dumpster fire just appears to be getting bigger and more out of control, but we have the receipts that the country can and does change. I am willing to fight for America to be the country that I deserve—that we deserve.

It also really helps that in moments of complete and utter distress and anxiety, my friends back in the States are doing amazing work to bring the promise of the US to fruition. I think about them every day and their very good work. I’m looking forward to joining them again when I get back, and doing what I can here to present a nuanced and complicated picture of the US to students and teachers and teachers-in-training. I’m doing what I can here to think and rest and be ready to go when I get back.

*thanks to my friend Jessica RM for sharing this with our writing group this week xo

Pingback: 2025-10-04 And Time Marches On | Naitnaphit Limlamai

Pingback: 2025-10-11 How We Remember Shapes How We Teach | Naitnaphit Limlamai